“It becomes clear what drove the inventor of 'political photomontage’”

Three questions posed to curator Christine Fischer-Defoy and Michael Krejsa, Director of the Visual Arts Archive of the Akademie der Künste, on the publication John Heartfield. Das Berliner Adressbuch 1950–1968.

Mrs. Fischer-Defoy, while preparing for the exhibition “John Heartfield – Photography plus Dynamite” in the Akademie der Künste, you found Heartfield’s address book from 1950 to 1968 – a real treasure trove of names! Were you aware beforehand of this treasure that was concealed in his estate?

Christine Fischer-Defoy: The biggest surprise was finding the address book itself. Michael Krejsa called me in January of 2019 asking if I could come by, because he had found something in the course of digitising the Heartfield holdings in his archives that might interest me. A few days later I had it in front of me: John Heartfield’s address book, compiled in the years following his return from exile! He asked me if I’d be interested in publishing this address book together with him. And whether I could imagine holding a joint lecture about preliminary research on this subject in the "John-Heartfield Haus” in Waldsieversdorf. There was no question about it: Of course I was interested!

The two of you worked through all the names, known and unknown, as well as the corresponding addresses. Which of the contacts surprised you most of all?

Christine Fischer-Defoy: The first surprise was the sheer amount of entries, from “A” for "Akademie der Künste“ on Robert-Koch-Platz to “Z” for “Z” for “Zwinger”, or kennel for the cocker spaniel, located on Moskauer Strasse in Woltersdorf. Altogether there are around 1,200 names with addresses and/or telephone numbers, some of the addressees have multiple entries. In the 1970s I had already been involved with Heartfield’s work, but it wasn’t until now, over 40 years later, that his correspondences with people in his address book allowed me to get to know John Heartfield as the lovable person that he was, surrounded by so many wonderful friends. It was particularly moving for me because I was lucky enough to have personally met some of these families and friends in the context of earlier projects on Nazi persecution and exile, including Heartfield's brother Wieland Herzfelde in East Berlin, his son Tom Heartfield in New York, Peter and Marty Grosz, the two sons of George Grosz in the US, George Wyland, the son of Wieland Herzfelde, who lived most recently in Switzerland.

Michael Krejsa: I had also come across some of them in the course of my work in the archives of the Akademie der Künste. Until the late 1990s many of them were still actively contributing to the archival holdings of the Visual Arts Archives and its neighbouring departments.

Christine Fischer-Defoy: Among the surprises for me were also numerous addressees from West Berlin who are still living in Berlin today, such as Reinhard Strecker, a pioneer in the education about Nazi perpetrators in the Federal Republic of Germany. To find out that he was corresponding with John Heartfield on this topic was a real “aha moment”.

Michael Krejsa: Another of these many moments of surprise was when we discovered the address book entry "OTZ (Schmalhausen) 327316 Charlottenburg Savignyplatz 5”, and simultaneously found one particular photo among the 3,000 private photos in the Heartfield Archives. The photograph [on page 161 of the book] shows, according to the writing on the back, a “visitor” talking to the photomonteur in an exhibition in the East Berlin Akademie der Künste at Robert-Koch-Platz in the year 1957. Through our archival research we learned that the visitor in question was the graphic artist and painter Otto Schmalhausen, also known as “OZ” or “OTZ”, who lived in the Western part of the city. Apparently, he had been invited to the opening of the first comprehensive Heartfield exhibition to be put on since the Second World War, which also signified the artistic and political rehabilitation of the “Dada monteur” in the GDR. This official ADN photo [Allgemeiner Deutscher Nachrichtendienst, or General German News Service, the official news agency of the GDR] thus revealed a completely different circumstance, which at the time was likely only known by insiders: namely the continuing existence of the old "Grosz-Heartfield-Conzern”, which since the 1920s also included, in addition to George Grosz and John Heartfield, Grosz’ brother-in-law Otto Schmalhausen. The mutual appreciation, both in terms of friendship and at artistic level, was to extend – despite all misunderstandings – well beyond the division of Germany.

The exhibition in the Akademie der Künste as well as the publication and commentary of the address book, provide a detailed look at John Heartfield, not only as an artist, but also on many different levels. Wherein do you see its importance? Why is it of particular interest for the public, still today?

Michael Krejsa: Just as the Berlin Address Book was about to go into print, an extremely informative and deeply unsettling documentary film was broadcast on Arte France Der Hitler-Stalin-Pakt. The historical record of collective failure in the 20th century reveals an extremely complex behind-the-scenes picture in the history leading up to the Second World War, the impact of which still resonates today in part. If you tie this timeline into the biography of Heartfield, whose most active stage of life coincides with this historical period, it becomes clearer what motivated the actions of the inventor of “political photomontage” and why he perhaps had no choice but to act. It is astonishing to see the person who was shaped by this period of history, a person who apparently found his unique role in art history between an uncompromising artistic stance and a staunch sense of humanity. And perhaps we come away with the insight that, especially in uncertain times, the humanity of our actions should remain a guiding principle. This must also be kept in mind when it comes to the bitter historical experiences that did not spare Heartfield. Virtuelle Ausstellung, catalogue and address book provide the renewed opportunity to explore the truth, life and work of the artist, complete with the lapses, the wisdom and, of course, with a dash of irony.

Interview: Sophie Charlotte Bentzien

An excerpt from the publication John Heartfield. Das Berliner Adressbuch 1950–1968 is available here (in German).

Further information on the exhibition “John Heartfield – Photography plus Dynamite”, on the accompanying catalogue John Heartfield. Photography plus Dynamite, on the virtual exhibition as well as on the biography of John Heartfield

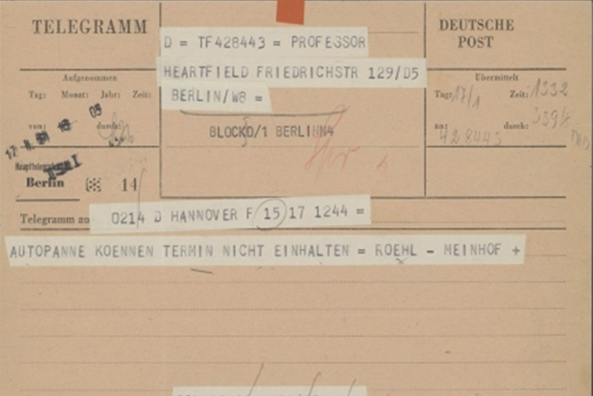

Additional reading: Lothar Müller on the story of Ulrike Meinhof’s telegram to John Heartfield: Süddeutschen Zeitung

The Federal Agency for Civic Education (bpb) supports the programme of events for the exhibition, in the context of which this digital offer was created.

Telegram from Ulrike Meinhof and Klaus Rainer Röhl to John Heartfield, Hanover, 1961. Akademie der Künste, Berlin, John Heartfield Archive, No. 415