„O write, as long as you can write!“

The autograph books of Susi Alberti

Sometimes it is the little things that stand up to the great injustice of history somewhat, symbolically at least: Susi Alberti’s three autograph books, which have been carefully preserved in many countries for a whole century, are a very personal memento of encounters with great artists, of both serious and light music, who were active in Berlin before 1933; they have survived the historical disasters of the last hundred years. Now Alberti’s heirs have brought these books back from Australia to Berlin, where the artists immortalised on their pages were once rigorously excluded from life in the city.

Susi Alberti was the younger daughter of Victor Alberti (formerly Victor Altstätter), a music publisher born in Miskolc (north-eastern Hungary) in 1884, who ran the Rózsavölgyi sheet-music publishing business in Budapest and, after moving to Berlin, founded the Alrobi, Alberti Musik, Ufaton, Dreiklang-Dreimasken, and Doremi music publishing houses. Before fleeing Germany, he was deputy treasurer of the German Music Publishers Association. He ran the Octava Verlag publishing house in Vienna up until 1938 and then, on the advice of the conductor Antal Doráti, fled with his family to Australia, where he again headed a publishing company. Susi Alberti was 21 years old when she arrived in Australia. She had no professional experience and initially worked in the countryside as an au-pair for the family of Yehudi Menuhin’s sister, Hephzibah Menuhin. As she had always lived in big cities in Europe, however, she soon moved to Melbourne, where she took a job at a bookshop which, not least because of her commitment, became a cultural centre in the city. It bore the telling name Hill of Content Bookshop.

Victor Alberti created the autograph books for his daughter immediately after she was born, as a kind of artistic family album. She was not even at school when the violinists Fritz Kreisler, Bronisław Huberman, and Carl Flesch gave her their autographs; she was just 6 years old when the pianist Paul Wittgenstein, the violinist Joseph Szigeti, the cellist Pablo Casals, the conductors Erich Kleiber (after the world premiere of Alban Berg’s opera Wozzeck) and Fritz Busch, and the composer Igor Stravinsky signed the book.

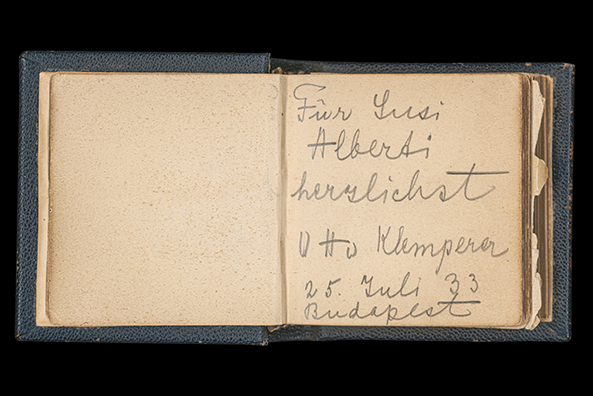

Another book contains the signatures of the con-ductors Otto Klemperer, Bruno Walter, Arturo Toscanini, Wilhelm Furtwängler, and Willem Mengelberg; the authors Thomas Mann, Stefan Zweig, and Ferenc Molnár (author of Liliom); and the composer Zoltán Kodály.

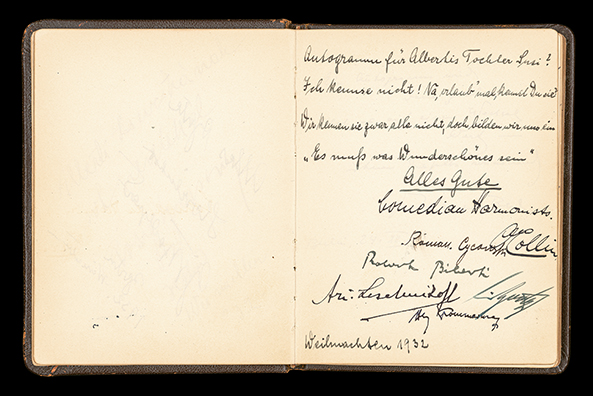

The fact that Victor Alberti first asked for entries on behalf of his daughter is more evident in another book dedicated to light musicians (Alberti clearly separated the spheres of “serious” and “light” music). For example, the members of the Comedian Harmonists wrote the following for Susi at Christmas 1932:

An autograph for Alberti’s daughter Susi?

I don’t know her! Well, if I may ask, do you know her?

We don’t know her at all, but we can imagine

It must be something wonderful

The last line is taken from the beginning of a famous song from Ralph Benatzky’s musical comedy Im Weißen Rössl, which had premiered in Berlin only two years earlier. This line is cited in an entry by Benatzky himself a few pages on, where in February 1933, while sitting on the night train with Alberti, he wrote the following:

Small poem on the train

It must be something wonderful

to be loved by you,

but when the train is moving, little Susi,

it makes it difficult to write,

though I don’t write very nicely anyway

at least

I have never smudged as much

as I did today on the trip from Vienna to Berlin!

Finally, in an entry dated 23 July 1933, the lyricist and librettist Robert Gilbert, known to us for his translation of the lyrics from My Fair Lady into German (or the Berlin dialect), holds a mirror up to his time. It takes him only two lines to do so, because he can trust that the reference to Ferdinand Freigligrath’s O lieb’, solang du lieben kannst (O love, as long as you can love) will be understood, as will the obvious double meaning of dichten (write poetry / seal up) and leck (lick / leak):

O write, as long as you can write,

The world is leaking enough!

The desire to play constantly with language while also satirising oneself is obviously a sign of the times. What is striking, however, is the way Victor Alberti dealt with artists: They knew he revered them, saw him as a friend, and if he was a businessman, he was also a trustee of their interests, a dealer who dealt in music without degrading art or artists as goods.

In Australia, Susi Alberti later married the son of a former singer at the Budapest Opera, Tamás Gábor, and was subsequently called Susanne Elizabeth Gábor. She did not consider the autograph books to be a completed legacy from her father, who had died in 1942, and occasionally presented them to artists in Australia (including violinist Yehudi Menuhin in around 1970) and supplemented them with individual pages, biographical notes, and selected correspondence. Mrs Gábor died in 2014 at the age of 95.

Through the mediation of Berlin-based Albrecht Dümling, who researches the condition of exile, Victor Alberti’s grandson, Charles Baré, who lives in Victoria, Australia, came into contact with the Akademie der Künste and visited its Music Archives in the summer of 2019 with his wife, Liz, in order to hand his great aunt’s autograph books over to the Academy on behalf of his family.

Author: Werner Grünzweig, Head of the Music Archives of the Akademie der Künste.

Published in: Journal der Künste 14, June 2020, p. 48-49