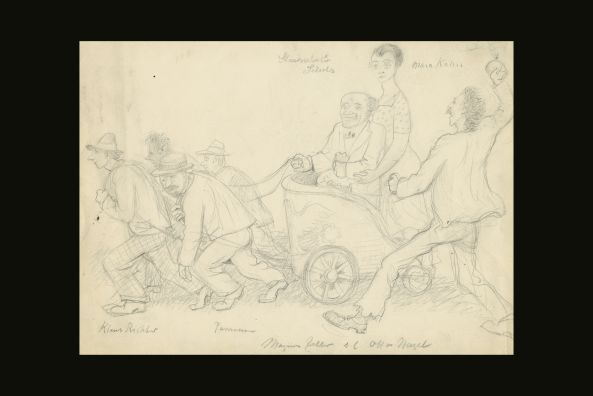

The Heinrich Schulz affair – an unknown drawing by Magnus Zeller

Why are artists – among them Klaus Richter and Hans Purrmann – towing a Roman carriage emblazoned with an imperial eagle? Why is the carriage being driven by a Herr Schulz, who is also holding a moneybag and is in the company of Maja Kahn standing behind him? And why is a man clearly identifiable as the painter Otto Nagel lobbing a bomb into party? The picture seems puzzling. But Magnus Zeller (1888–1972), in this hitherto unknown and undated pencil drawing, took up an affair of the German Art Association in the closing years of the Weimar Republic. He dedicated the sheet – recently acquired by the Archives of the Akademie der Künste – to one of the protagonists, “s[einem] l[ieben] Otto Nagel” or “his dear Otto Nagel”.

The Deutsche Kunstgemeinschaft (German Art Association) was founded in the spring of 1926 on the initiative of Heinrich Schulz, a member of the German Social Democratic Party (SPD) and State Secretary in the Reich Ministry of the Interior. In addition to Schulz and others, the working committee included Hans Baluschek, Charlotte Berend-Corinth, and the art writer Max Osborn, and the honorary committee included many people, among them Käthe Kollwitz and Max Liebermann. Financially supported by the Reich, the Deutsche Kunstgemeinschaft held regular exhibitions in the Berliner Schloss (Berlin Palace) from May 1926, and later at other locations in the capital and in other German art centres. The aim was to support contemporary artists by encouraging purchases of art. At the same time, the intention was to bring original works to the attention of broad sections of the population. On display were all styles of oil paintings, watercolours, pastels, graphic art, and sculpture. In the event of a purchase, a fund established by the Kunstgemeinschaft enabled the artist to receive the entire sum immediately. The buyer could pay off the amount in installments. Art hire and subscriptions from the Kunstgemeinschaft’s collection were also available. In addition to private prospective buyers, the purchasers of the works included municipalities, public authorities, and museums. The works were not only by young, unknown artists, but there were also successful ones among them. In October 1930, for example, the press reported the City of Danzig’s purchase of Otto Dix’s Portrait of Heinrich Sahm for 4,000 marks.

But several artists complained of being severely disadvantaged by the Kunstgemeinschaft’s low purchase prices. Magnus Zeller and Otto Nagel whose archives are managed at the Akademie der Künste, were among the critics, although, as the Kunstgemeinschaft’s annual reports show, these artists themselves exhibited and sold works through the association. However, the sales lists reveal large price differences between certain artists and works. For example, Nagel’s four paintings, sold up until the end of 1928, fetched 200 to 360 marks each, while Klaus Richter, Magnus Zeller’s childhood friend, received 2,000 marks from the Ministry of Culture for his painting Der sterbende Torero (“The dying torero”). Richter, a student of Corinth, later became Chair of the Verein Berliner Künstler (Association of Berlin Artists). He is best known for his two enigmatic portraits of Adolf Hitler, which are in the Stadtmuseum Berlin (Berlin City Museum) and the Deutsches Historisches Museum (German Historical Museum). Henri Matisse’s student Hans Purrmann also exhibited at the Deutsche Kunstgemeinschaft, including in the autumn exhibition Neue Deutsche Kunst 1930 (New German Art 1930), alongside Richter and Zeller; no evidence of sales via the organisation has so far been found.

But what is the bomb all about? In the left-wing socialist Berlin newspaper Die Welt am Abend, Nagel published articles on 20 and 21 March 1931, accusing Heinrich Schulz of nepotism and wasting public money. Even in 1927, Nagel had claimed in the Sozialistische Monatshefte that the organisation’s administrative costs were out of all proportion to its turnover. And now he accused Schulz and his private secretary and partner Maja Kahn of high travel expenses, questionable buying and selling practices, the purchase of a new car, and the refurnishing of palace offices. In addition, he claimed Schulz gave preferential treatment to artists who were not in need and who already had a steady market. This is probably one of the reasons why Zeller “harnessed” Purrmann alongside Richter in his drawing.

Nagel’s accusations sparked a major scandal. At the annual meeting of the Kunstgemeinschaft and in an open letter, Schulz had to explain his position on the use of the funds. Although the Kunstgemeinschaft gave him a vote of confidence, another, probably also politically motivated, move was made against him afterwards by an official of the Ministry of the Interior. Schulz repudiated all the allegations. Nevertheless, as of August 1931, the Ministry’s regular grants were discontinued. In September, the longtime treasurer, the banker Hugo Simon, resigned. Schulz refused to resign from the management of the Kunstgemeinschaft, but died unexpectedly in September 1932. The Deutsche Kunstgemeinschaft was dissolved in August 1936.

Author: Anke Matelowski, Research Associate in the Visual Arts Archives of the Akademie der Künste.

Published in: Journal der Künste 19, November 2022, p. 48-49